By Mariana Malgay

Communication Coordinator for the Hora de Obrar Protestant Foundation*

The land without evil

The province of Misiones is located in northeastern Argentina, near the border with Brazil and Paraguay. It is one of the smallest provinces in terms of area, but one of the most densely populated. In this triple border, native, Guarani, Polish, German, and Italian cultures, identities, and languages intertwine.

Misiones is known, among other reasons, for what remains alive of its lush Selva Paranaense or Atlantic Forest, which is part of the Gran Chaco region and is home to numerous species of animals and plants. Additionally, it is famous for the Iguazu Falls, an impressive waterfall that is considered one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World.

The Atlantic Forest hides within its thickness a surprising biodiversity, which unfolds on the eastern coast of Brazil and penetrates inland towards Argentina and Paraguay. More than 148 million people are nourished and dependent, both socially and economically, on the services provided by the Atlantic Forest, such as the provision of water, energy, and soil protection. This natural treasure is also home to a great variety of life, which includes seven percent of the world’s plant species and five percent of vertebrate animal species. Many of these species are endemic, which means that they do not exist anywhere else on the planet, making it even more valuable and worthy of protection.

The story goes that the Guarani peoples, native to this region, believed in a god named Tupa, who had created a perfect land for human beings, where there was no pain, suffering, or disease. However, humans, by straying from divine mandates, lost access to that perfect land and fell into a world of pain and suffering.

Despite this, the Guarani people continued to believe in the existence of a «Land without Evil,» a sacred place where human beings could live in harmony with nature and achieve perfection. And it was in the province of Misiones where they found the closest land to that ideal. The natural beauty and biodiversity of the region were so extraordinary that they identified it as an extension of the «Land without Evil.»

There is a harsh reality, though. The loss of biodiversity, excessive deforestation, and expansion of the agricultural frontier in Misiones pose a stark contrast to the image of an earthly paradise associated with this region. Poverty affects more than half of the population in the province, casting a dark shadow over the scene. Thus, the need to protect and conserve the Selva Paranaense, not only as a natural heritage but also as a livelihood for local communities, becomes imperative. Only in this way can the biological and cultural richness of this land be preserved, and a sustainable future be built.

Their ancestral knowledge can contribute greatly to the protection of the common home, understood as the Earth and its ecosystem. These indigenous peoples have developed knowledge and practices over centuries of interaction with nature, and they maintain a worldview of harmony among beings from which Christians have much to learn.

The forest as a classroom is life and joy

Santo has been an indigenous assistant teacher for more than ten years. He works at the Takuapi intercultural school, where the homonymous indigenous community lives, composed of about forty Mbya families on the outskirts of Ruiz de Montoya, an agricultural and forest town about one hundred and twenty kilometers north of the provincial capital city, Posadas.

In Misiones, more than thirteen thousand people identify themselves as belonging to indigenous peoples, according to official data from 2010. Of these, almost seven thousand four hundred identify themselves as Mbya-Guarani, belonging to the Tupi-Guarani linguistic trunk. Anthropologist Morita Carrasco explains that more than five centuries ago, these peoples settled along the Amazon, Paraná, and Paraguay rivers, in what are now the states of Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, and some areas of Uruguay. They had their first contacts with Spanish conquerors during the 16th century, while the Society of Jesus began the religious conquest of this people in missions and reductions in the Republic of Paraguay, southern Brazil, and the provinces of Corrientes and Misiones. However, the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 caused the dispersal of the Mbya throughout the jungle.

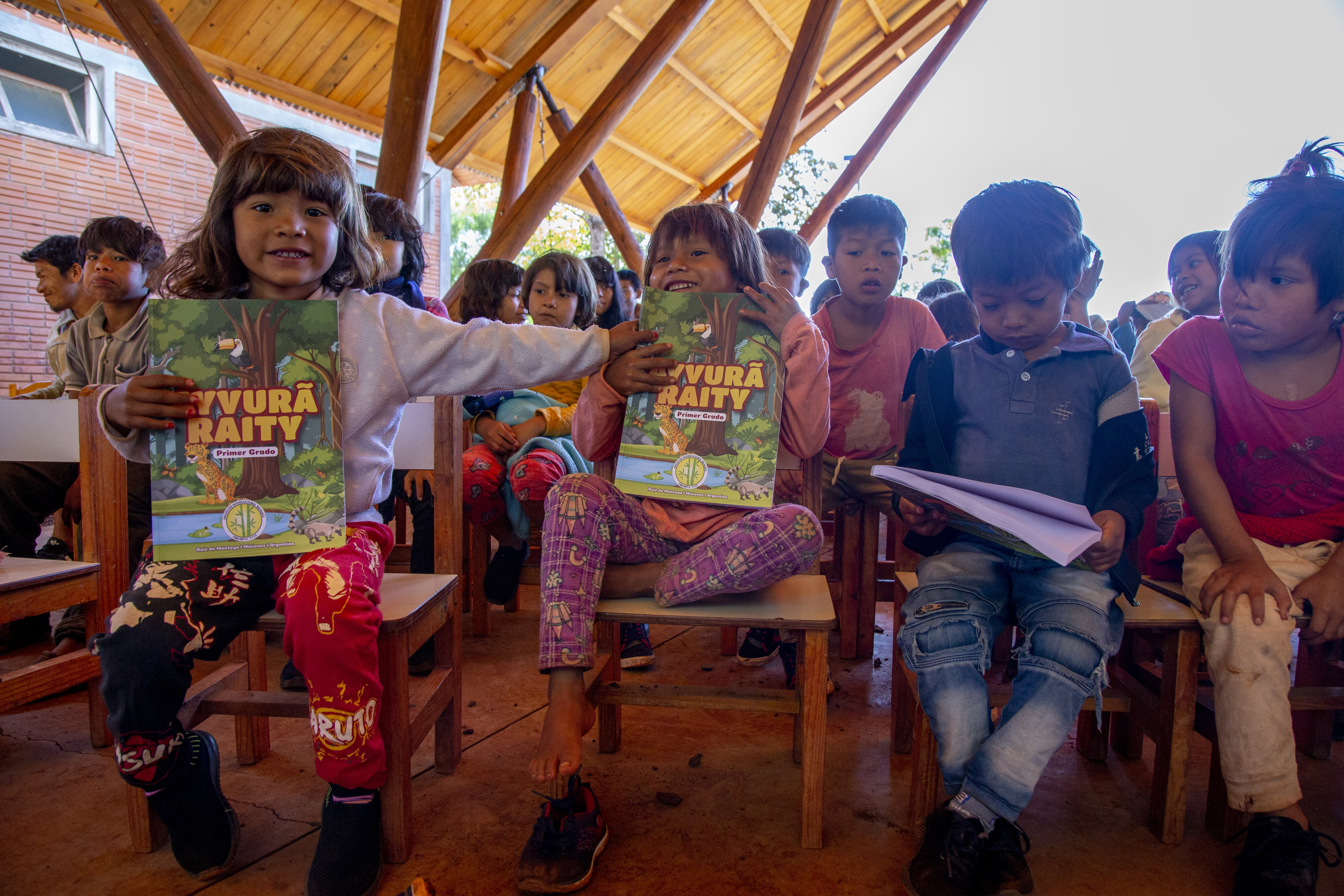

«Santo is a saint. As his name indicates,» says the school’s director, Alicia Novosat. He recently participated in the creation of a bilingual manual to teach the alphabet together with the teacher Karina Schmidt and the indigenous teacher Mario Acosta. When she describes what she felt upon seeing his name on the cover of the educational material, she smiles and can hardly find words. «It’s a satisfaction for us to work better with the kids.»

Santo thinks of the forest and explains what it means for Mbya culture in an eloquent way. «The forest for us is life. Not only human life, but also for the animals, for the birds. And it is joy. We cannot live without the forest. I always remember the phrase my grandfather told me when I was twelve: ‘the forest is life.'»

Santo thinks of the future as he lives in the present: with hope in the children. «Today, as a teacher, I’m trying to teach these things to the kids so that they also know how to take care of what’s in the world.»

He speaks with a calm voice and full of ancestral wisdom. «The tree has its God. Every animal has its God. That’s why our grandfather also teaches us that if we go to the forest, we have to take care and be careful,» he explains. «If I take the machete and go, I have to take only what I need, not go and cut and cut, because the spirit doesn’t like it. We have to ask the spirit: ‘today I’m going to cut this wood because I need it for some things’,» he says.

His eyes shine with sadness as he talks about deforestation and the loss of nature in his land. «What worries me is that sometimes owners come and deforest, cut down trees, and nothing is left.»

But his hope is still alive. «My wish is that we continue with strength and wisdom so that some of the kids in this community set an example. That they don’t forget their culture, even if one of them becomes a professional from a school,» he reflects. «That they fight, doing the fight like the mburuvicha* are doing now.»

Santo, a guardian of nature and bearer of ancestral knowledge, reminds us of the importance of caring for and respecting the balance of life on Earth. His words invite us to reflect on our relationship with the environment and how we can learn from indigenous cultures to protect and preserve the common home we share.

*»The mburuvichá (commonly known as cacique) (…) is their political leader. They are heads of extended families and, being hereditary, they are practically representatives of lineages. They are responsible for activities that contribute to the material life and well-being of the members of the village, and above all, they maintain the relationship with non-aboriginals.» Free translation: Morita Carrasco in «Towards intercultural justice in Misiones.»

Water, source of life and spirituality

Raindrops fall gently on the Ko’eju Mirî village, one of the sixteen indigenous Mbya Guarani communities reached by the Tape Porã project of the Hora de Obrar Foundation in the province of Misiones. Thanks to this project, a recent improvement in the spring protection work was carried out and the electrical wiring was installed.

The prior consultation was essential in this process. It is a right that seeks to obtain the free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous peoples regarding any measure or project that may affect their territories, natural resources, or ways of life. That is why a participatory diagnosis was carried out on access to basic services, and based on the results, a proposal was presented to the community to work together.

«The indigenous people themselves are working and supporting the project, and that is important. One has knowledge and brings the need, concern, and together we develop the project.» Francisco Medina, a community member, recalls the process while sitting inside a classroom with corrugated metal roofs, where the sound of water can be heard. He knows very well the importance of respecting this specific right of indigenous peoples: «We have experienced many promises from non-indigenous people that have not been fulfilled. Sometimes, we accept a project with doubts.»

He also knows that the water that rains today and also springs from the ground is life, and it must be protected. «Today we can no longer take water from a stream that comes from who knows where. The water is contaminated, and it brings many diseases. That is why we fight for water; so that families and the community have their own better, healthier water. That is what we need most in the community.»

The spring is located away from the houses, about eight hundred meters away. For years, women in the community walked daily to the spring to get water to meet their basic needs: drinking, washing clothes, or cleaning food. With buckets full of water in their hands, they sometimes had to make the journey several times a day.

But the life of the community changed with the water and electricity works. Sandra Benitez, one of the community members, smiles when she remembers the days before and celebrates the improvement for the daily life of women. Now she can use the nearby fountains close to her home and not have to travel so many meters to get water. «Women in the community are happier. I used to see someone passing by with a bucket, and I automatically grabbed one and left because we had the habit of going together to fetch water. From what I see, they are doing well, happy, content, to have it at home.»

She also remembers what her life was like before: «I used to go many times to get water. It was very difficult for me since my husband works and comes at noon. Today, having it at home really helps me,» she celebrates. «My life has improved.»

Sandra now dreams of a community space where women can cook together and share time with their children. «I don’t know why I always have this thought of wanting to gather among women and have a place to cook together and be with the kids. I don’t know why I have that thought of wanting to have that,» she expresses with nostalgia and hope in her voice.

*About the Hora de Obrar Protestant Foundation

Hora de Obrar works for social and environmental development in Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. It is an initiative of the Evangelical Church of the Río de la Plata, inspired by a commitment of faith for a fairer, more equitable, and supportive world. Therefore, since 2014, it has developed and supported social and environmental projects to promote and defend the rights of people in situations of greater vulnerability and to preserve the environment for future generations. Hora de Obrar works based on 5 thematic areas: community development, climate justice, indigenous peoples, gender justice, and diaconal strengthening.

More information at www.horadeobrar.org.ar